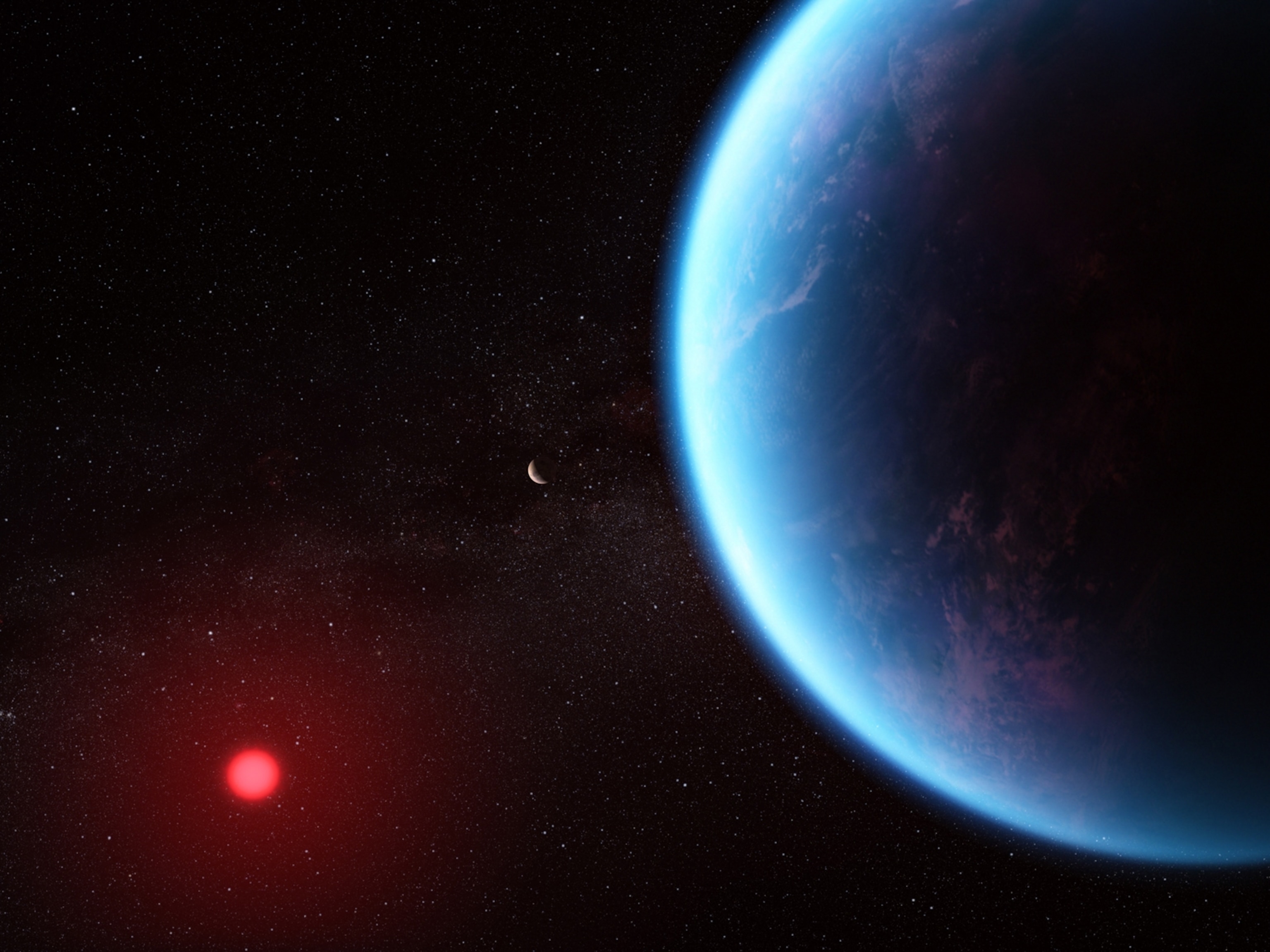

Uranus, the seventh planet from the sun, may initially look like a bland, blue-green ball. But there's a lot to love about the icy giant, from its 13 rings to its 27 known moons to the fact that it may even rain diamonds from its hazy atmosphere.

Uranus was the first of three planets in our solar system discovered thanks to the invention of the telescope. In March 1781 British astronomer Sir William Herschel spotted the glinting object in the sky, initially mistaking it for a comet. When it was accepted as a planet years later, Herschel lobbied to call the discovery Georgium Sidus after King George III. Instead, it got its official name from the Greek god of the sky, Uranus, who was both son and husband to Gaea, the goddess of Earth.

The planet Uranus was so hard to find in part because it is a whopping 1.8 billion miles away. But it is actually the third-largest planet in our solar system, and is roughly four times wider than Earth.

Like Saturn, Jupiter, and Neptune, Uranus is a big ball of gas, often called a jovian or gas giant world. Uranus owes its vibrant blue-green hues not from unusual oceans but from an upper atmosphere flush with methane, which absorbs the sun's red light and scatters blue light back to our eyes.

The rest of planet's atmosphere is largely made of hydrogen and helium, with scant amounts of ammonia, water, and methane. Trace amounts of hydrogen sulfide also hint that, if you could visit this distant place without a spacesuit, the planet would smell like rotten eggs. While Saturn wears the crown for the least dense planet in our celestial family, Uranus is not far behind: Most of its mass is made up of an icy dense fluid of water, ammonia, and methane.

Side spinner

One particularly curious feature of Uranus is its off-kilter positioning. The gas giant is tipped on its side, spinning on its axis at nearly a right angle to its orbital path around the sun, which requires a lengthy 84 Earth-years to complete. Scientists believe that this unexpected tilt is the result of a massive collision with something the size of Earth far in the planet's past.

Thanks to its sideways turn, Uranus has some wild seasons, with the sun blazing across each pole for 21 Earth-years at a time while the opposing side lingers in the pitch blackness of space. And that's not the only strange thing about its spin. Like Venus, Uranus has what's known as a retrograde rotation, turning on its axis in the opposite direction to the rest of the planets.

Also topsy turvy is Uranus' magnetosphere, the magnetic field enveloping the gaseous world. It's tipped nearly 60 degrees from the axis of rotation. That sets the planet's auroras out of line, making them appear far from the poles, unlike those on Earth.

Beneath the blue

Only one spacecraft, Voyager 2, has ever flown by Uranus at close range. The craft came as near as 50,600 miles to Uranus' cloud tops in 1986, giving scientists their first detailed peek at both the planet and its many curious moons.

During that encounter, Voyager 2 snapped what is perhaps the most famous picture of Uranus—a pale turquoise orb in a sea of darkness. But follow-up observations have since shown that there's more there than initially meets the eye. Voyager 2 captured the planet during its solstice, when one pole was bathed in sunlight and so kept a constant temperature. The lack of thermal change keeps winds to a minimum, making the planet seem bland and static.

But when Uranus moves toward its equinox—a period of time when day and night are of equal length—the sun illuminates the planet’s equator. Different parts of the orb absorb the sun's rays during its 17-hour-long day, and the difference in temperature drives a swirl of storms.

What's more, Uranus's methane acts like a blue shroud, obscuring the features that lie below to telescopes operating in optical light. Infrared images, however, can pierce the layer and peer at the swirl of clouds that hide below.

There's still much more to learn about these tempests. In 2014, between Uranus's infrequent equinoxes, astronomers using the 10-meter Keck telescope spotted eight stunning squalls below its blue blanket. Scientists suggest that perhaps these vortices are rooted deeper in the atmosphere, like the storms of Jupiter. But to know for sure, researchers would need a closer look.

Voyager 2's flyby also revealed 10 previously undiscovered moons and two new rings, and its data continued to be a trove of information long after the spacecraft sailed by. In 2016, scientists reexamining Voyager 2 data discovered the possibility that the planet may harbor two more tiny moons.

Though no plan is currently in the works to go back for an even closer look, Uranus likely holds many more secrets just waiting to be discovered.

NASA Solar System Exploration: Uranus

NASA JPL: Voyager's Uranus Approach

Space.com: William Herschel Biography

NASA's Starchild Question of the Month

Berkeley Research: Amateur, professional astronomers alike thrilled by extreme storms on Uranus

University of Texas McDonald Observatory: Big Blue Planet

Forbes.com: Why Is Uranus The Only Planet Without Interesting Features On It?

Tufts: Uranus and Neptune Fundamentals